Table of Contents

Chronic stress is a silent killer that we don’t talk about enough. In biology, we think of high blood pressure as a silent killer because it can lead to a heart attack or stroke without giving any warning. Chronic stress can be a cause of high blood pressure, but also of poor functioning of the immune system, the development of several diseases and accelerated aging. Here are some explanations to better understand these phenomena. I believe that the more knowledge we have about this topic will then allow us to be more motivated to take action to prevent or reduce its impact on our daily lives.

Stress is natural. It is a physiological process, necessary for survival, but felt uniquely by each person. Unique because our means to cope with it, or not, depend on the type of stress, our knowledge of its presence, our personality and our situation as an individual. Its consequences on health, as on aging, are however, universal. Let’s start by understanding its impacts on health.

Chronic stress, the silent killer

Chronic stress results from prolonged and repeated exposure to conditions that cause us to secrete stress hormones. These hormones have very specific and beneficial roles to play, but their overproduction leads to exhaustion, weakening of the immune system, and lowering the effectiveness of many other systems. We are talking here about stress that is felt when at risk, during an emergency, and not one that can push us to perform (which is often seen as good and bad stress; let’s focus on the bad). The physiological response to stress exists to enable us to fight or flee. We determine when a situation is dangerous to our survival and we respond by mobilizing energy, increasing the rate and force of the heartbeat, and producing adrenaline to speed up our actions and decisions. This is an alert state.

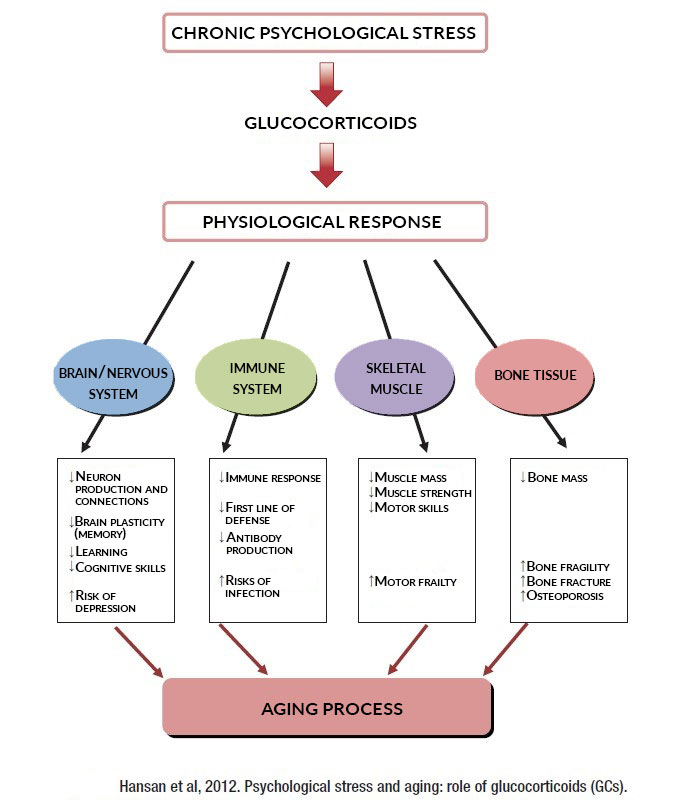

When the alarm is triggered, the brain sends out requests for the production of glucocorticoids. This is called the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA axis) that manages the stress response. The stress response – the alert state – results in an increase in blood pressure and heart rate, all of which are handled by our brains. Depending on the level of perceived stress and our capacity for personal resistance, the response will be more or less important. However, if stress persists, this physiological state can promote the onset of certain diseases, aggravate them and most importantly, create a large number of symptoms, both physical, emotional, and behavioral. The excessive production of glucocorticoids is caused by chronic stress and this accelerates aging and leads to what is called adrenal fatigue.

The maximum alert state

This momentary natural reaction therefore becomes problematic when it is chronic or repeated with too much frequency. This is a state of emergency: it is not good to be in a state of emergency all the time. Chronic stress not only affects the immune system, but also a large number of physiological processes. Glucocorticoids are hormones that regulate a large amount of physiological activity. The best known is probably cortisol. Cortisol is often referred to as the stress hormone because stressed people have higher levels of cortisol. Cortisol is used, among other things, to stimulate energy production during stressful events. It was noted that the production of glucocorticoids (GC) elicits several physiological responses typical of aging. GCs interfere with synaptic plasticity (the ability to rearrange our neurons). This is what makes it easier for us to forget when we are stressed for long periods of time. Likewise, GCs cause muscle atrophy, reduce the effectiveness of the immune system, and increase bone resorption. Thus, GCs could even be the cause of certain diseases associated with aging. The following figure summarizes several physiological effects of GC and their link with the aging processes.

Remember the dangers

The effects of stress on the brain and nervous system are numerous. The fact that stress reduces the production of nerve connections is a very concerning observation. It also reduces the reorganization (neural plasticity) that is necessary to learn or memorize. Yet it is able to induce recurring thoughts or memories related to an event that we have perceived to be extremely dangerous. This ability is an evolutionary adaptation that allowed Cavemen to remember the bear’s presence in the third cave on the left. Unfortunately, today this ability is the source of recurring thoughts or memories of difficult events.

Altering metabolism and enabling hunger

Recent studies tend to show that psychological stress, which is differentiated in biology from physiological stress which can be caused by heat for example, strongly influences the behavior of our mitochondria, the small energy powerhouses of our cells. Stress hormones modify the energy mechanisms of our mitochondria while encouraging them to change certain epigenetic factors and to produce certain pro-inflammatory mitokines (mitochondrial cytokines). This may partly explain the weight gain and fatigue, but it is not the only explanation.

Without going into detail, stress would alter our ability to produce energy, while causing hunger and facilitating the reward mechanisms associated with eating. This is another hormone called ghrelin, which largely regulates appetite, is heavily involved in the processes of stress management and resistance to chronic stress. The link between appetite and stress is easy to understand. On the one hand, when one is hungry, anxiety rises because it is a basic problem to be addressed, a case of survival (in the days of the cavemen). On the other hand, eating is strongly associated with the brain’s reward mechanisms giving the feeling of wanting more. Thus, stress stimulates the appetite and the reward center associated with eating, which makes us feel reassured while eating. A great principle for gaining weight.

Reduction in the effectiveness of the immune system

Unfortunately, chronic stress will directly reduce the effectiveness of the immune system, both the first line of defense, and the production of antibodies. The production of antibodies is part of the second line of defense, which is acquired immunity; acquired following a vaccine or a first infection. This makes it easier to catch the flu, a cold, or have pneumonia when you are under chronic stress. However, stress is not a form of magic that you cannot react to. Stress is felt, managed and lived.

Manage stress better

First and foremost, stress management is a point of view. If you’re stuck in a traffic jam and you’re running late, it doesn’t help to engage in road rage, yell, or worse, get out of your car to hit the driver who just cut you off! No, it does absolutely NOTHING! You have to breathe through your nose and look at the situation differently. When you can’t control a situation, you have to make sure the situation doesn’t control you! Every time the stress levels increase, health takes a hit … such as catching a cold.

It is important to develop our resilience. It refers to several “ways of looking at things” that help us relieve the pressure we constantly feel. For example:

- Remember that you can adapt, that you have faced difficulties in the past and have been through them successfully.

- Try to think calmly, but proactively.

- Tolerate uncertainty; it is normal not to know how things are going.

- Avoid the media which only dramatizes the situation.

- Remember that humanity has gone through difficult times in the past.

As stress is unique to each person, it is also important for each person to get to know themselves well and to develop tips to better manage stress. The important thing is not to apply as many as possible, but to try them out and keep the ones that suit us best:

- Accept situations that cannot be controlled.

- Strengthen social ties (talk about your feelings).

- Physical activity.

- Meditation/relaxation.

- The consumption of omega-3s (food or in supplements).

- Watch out for caffeine (coffee and energy drinks).

- Cut down on refined sugars.

- Increase your intake of antioxidants (fruits and vegetables).

- Improve your sleep (sleep hygiene)

- Use quality supplements as needed:

- For chronic stress, depression and fatigue: Vitoli Energy.

- For anxiety, momentary or current: Vitoli Stress and Anxiety.

- For the nights: Vitoli Sleep or Vitoli Stress and Anxiety.

Overcome stress

Overcome stress only because you have to live it and not run away from it or avoid it. Many health problems are directly or indirectly related to problems with stress. It is important to be aware of this and to try to apply approaches that can help us to live better. In closing, a positive attitude and the decision to live better is the first step in the right direction.

References:

- Abizaid A. Stress and obesity: The ghrelin connection. J Neuroendocrinol. 2019 Jul;31(7):e12693. doi: 10.1111/jne.12693. Epub 2019 Feb 19. PMID: 30714236.

- Al Massadi O, Nogueiras R, Dieguez C, Girault JA. Ghrelin and food reward. Neuropharmacology. 2019 Apr;148:131-138. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2019.01.001. Epub 2019 Jan 5. PMID: 30615902.

- Bradbury J, Myers SP, Oliver C. An adaptogenic role for omega-3 fatty acids in stress ; a randomised placebo controlled double blind intervention study (pilot) [ISRCTN22569553]. Nutr J. 2004 Nov 28 ; 3 :20.

- Brillon, P. 2020. COVID-19 Maximisons notre résilience. La Presse + 13 mars 2020.

- Ditzen B1, Heinrichs M2., 2014. Psychobiology of social support: the social dimension of stress buffering. Restor Neurol Neurosci. Jan 1;32(1):149-62.

- Hasan KM, Rahman MS, Arif KM, Sobhani ME. Psychological stress and aging: role of glucocorticoids (GCs). Age (Dordr). 2012;34(6):1421–1433.

- Picard M, McEwen BS. Psychological Stress and Mitochondria: A Conceptual Framework. Psychosom Med. 2018 Feb/Mar;80(2):126-140. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000544. PMID: 29389735; PMCID: PMC5901651.

- Stenman LK, Patterson E, Meunier J, Roman FJ, Lehtinen MJ. Strain specific stress-modulating effects of candidate probiotics: A systematic screening in a mouse model of chronic restraint stress. Behav Brain Res. 2020 Feb 3;379:112376. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2019.112376. Epub 2019 Nov 22. PMID: 31765723.